Perhaps it was the dizziness of cinephilia. When I first saw Wim Wenders sitting in the front row at PVR Plaza, Connaught Place, he briefly looked like a Jat from Shahpur Jat. He had that assured stillness, the quiet authority of a man who has seen things. And like all great desi taus, he wore sports shoes under serious attire, always prepared for a sudden walk, the real king of the road.

Of course, Wim isn’t a tau. If anything, he leans more towards Taoism.

Wenders is, of course, one of cinema’s greats, and his most famous film remains Paris, Texas. If you’re a Letterboxd regular, you’ve probably logged Perfect Days too. And if you’re a true cinephile, perhaps you’ll appreciate both—Wim’s Perfect Days and Himesh’s Tandoori Days.

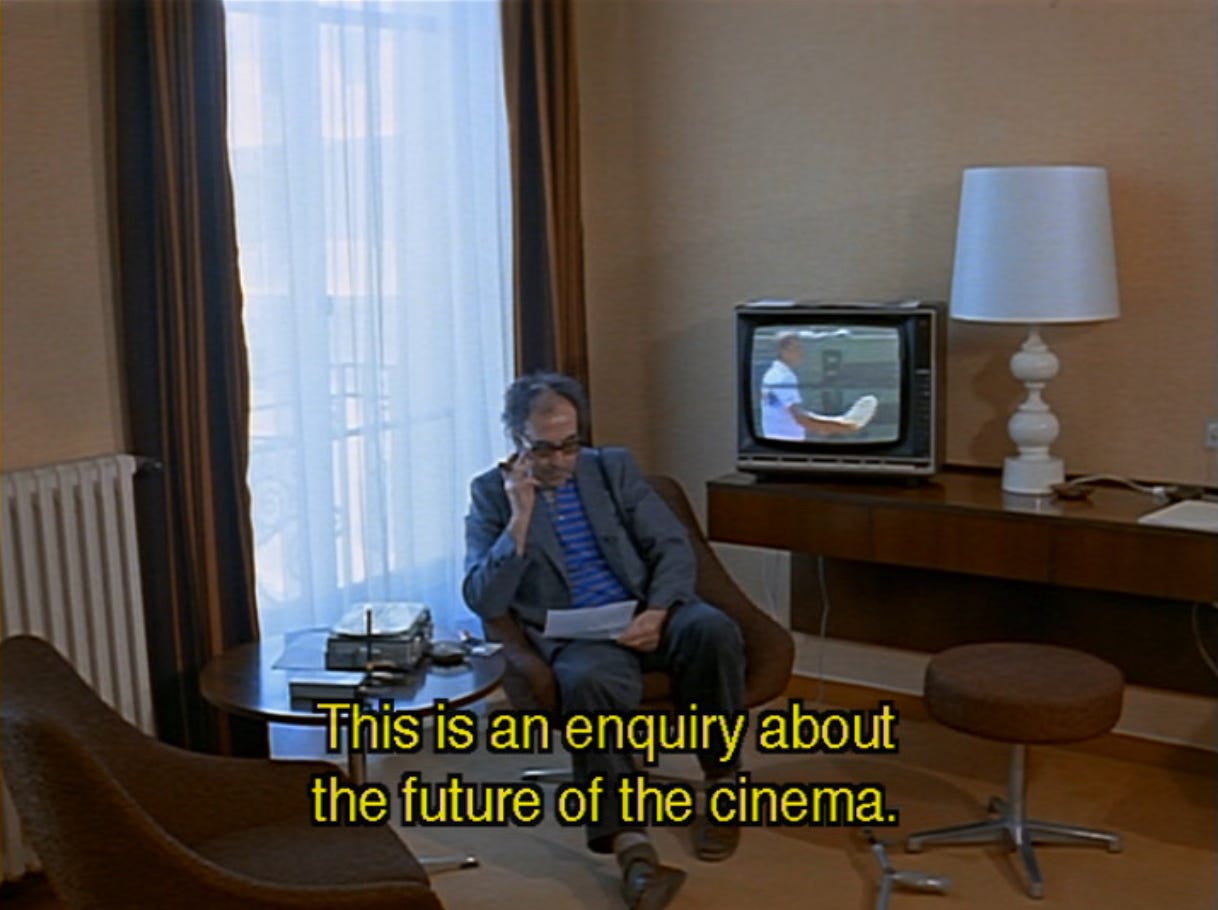

I first watched Wenders' retrospective as a student at FTII, Pune, sometime in 2013—twelve years ago, though it feels like another geological era. Among his films, the one that remained with me was Room 666.

During the 1982 Cannes Film Festival, Wenders asks a number of global film directors to, one at a time, go into a hotel room, turn on the camera and answer a simple question: “Is cinema a language about to get lost, an art about to die?

The lineup included Godard, Spielberg, Fassbinder, Herzog, Antonioni. In today’s terms, it was essentially a self-podcast, without the host.

The answers were suitably profound. Some mourned the inevitable decline of the medium, others argued that cinema was simply evolving.

The question feels even more urgent today, but not in the way Wenders imagined. The issue is no longer whether cinema is dying but whether the very definition of cinema has been disjointed. Are YouTube videos also cinema? What about TikTok videos capturing absurd ? The internet has already has a meme template of Scorsese’s face with the words “This is Cinema,” applied generously to anything that momentarily touches the boundries of cinematic moment. Is cinematic moments now randomly sprinkled in zig zag fashion on terrains on internet.

Incidentally, the venue where Wenders’ masterclass was held (CP, Delhi) also happens to be a gathering spot for ex-TikTokers, now rebranded as Instagram reelers and MX Takatak enthusiasts. Every day, they fill the park, refining their moves to achieve the state of virality—the only form of spirituality that truly matters in the digital age. I wonder if Wenders, in the spirit of Ozu, would have quietly filmed them too, as he was walking through CP, watching their movements with the same patience he reserves for Tokyo’s laundromats.

The conversation with Shivendra Singh Dungarpur started with an unusual observation—why, despite being German, was Wenders more influenced by American filmmakers than by his own country’s cinematic tradition? Wenders responded without hesitation. He had no interest in being bound by his nation’s tradition and roots. In fact, he found parts of German history repulsive. He recalled a childhood teacher who had a mustache suspiciously similar to Hitler’s and later realized how much that resemblance extended beyond the face. Cultural pride, he suggested, was optional. He later said he made more films and better films once he was out of Germany.

It was a rare thought in a time when cultural revival is a full-time industry, and the past is a raw material constantly being sharpened into a weapon. Wenders had no such burden. He saw no need to claim a glorious lineage, no urge to romanticize the soil he came from. My own theory is that, finding no peace in his own heritage, he outsourced his spiritual needs to Japanese Zen—like a man who knew that wandering, being on the road, and discovering new things is what makes a human, human.

This is particularly relevant in today’s discourse, where everything is dismissed as the “Western gaze.” But what, really, is the regional gaze? What is the national gaze? And why must artist be tied to it? Isn’t the very idea of the sticking the gaze comes with a faint odour of conservatism ?

At one point, when Wim mentioned Japanese filmmaker Ozu and the theater clapped, he looked genuinely surprised. He scanned the room and asked, "Do people know Ozu here?" I don’t know why but imagined him watching us leave the hall, expecting us to take the Metro home and, in the true spirit of the national gaze, break into a Naatu Naatu routine in our living rooms.

Wenders made a clear distinction between the personal and the private. The world, he said, is obsessed with the private—journalists chase scandals, the juicy details, the stuff that fits into a headline. But the personal, the quiet interior world of a person, is rarely explored. That, he argued, is where real art comes from. And when artists understand this, it shows—not just in what they create, but in how they see everything around them.

He also spoke about restriction as a creative force. The more money a filmmaker has, the less personal their work becomes. Money invites decision-makers, and decision-makers want returns. Slowly, cinema stops being cinema. It turns into a product—one more shiny thumbnail in the graveyard of Netflix.

I love how he puts it—cinema isn’t about storytelling, it’s about situations. What makes a great film isn’t just what happens to the characters, but how a filmmaker shapes a moment by blending the personal. Stories, he says, never really happened in his life. But interesting situations, plenty.

At one point, we reached peak Delhi. Someone in the audience asked a question that could have triggered lesser men, especially a Mumbai-Bandra-Versova filmmaker. She said: I didn’t like the ending of Paris, Texas, why did that character leave ? it makes no sense whatsoever.

She wanted the couple to reunite.

For a moment, I expected Wenders to be irritated, maybe even offer an angry dismissal. But his Zen discipline, I realized, isn’t some Instagram bio philosophy like wanderlust, old soul, sunsets. It’s the real thing. He simply said, “Sometimes, leaving is also a form of love.”

Nothing more needed to be said after this!

Thank you, Wim Wenders, for being a breath of fresh air in the world's most polluted city.

Hope you had a good time reading this. Substack doesn’t pay, and the payment system is basically broken. So if you liked this, consider becoming a monthly patron on Patreon or joining the YouTube membership. This unlocks a bunch of member-only podcasts and other exclusive stuff. Thanks!

Lately I have this feeling that not only individuals dont really exists in our society, they have stopped existing in Indian cinema also. All movies now exists boldly in fantasy of dumbest kind. An innocent viewer might feel that perhaps its a parody that makes fun of its character .. but its not .. we are in a world.. where we write dumb character and in order to sincerely enjoy them .. everyone else intentionally becomes dumb while watching it... and the movie becomes real worldly!

An individual with personal/internal world is an alien concept for our filmmakers... it seems increasingly clear that perhaps we are living in the worst phase of Indian cinema.

Last set of movies that can still be called as such that I remember were around Ankhon Dekhi, perhaps ..

Your insane ability to connect Wim Wender's attire to Haryanvi roots about a filmmaker who has no interest in being bounded by his country's traditional roots is just crazy 🤣