The Philosophy of Checkmate: Amit Dutta on Chess and Life’s Lessons

A Game That Offers Fascinating Lessons on Life

This guest article is written exclusively for culture cafe by the renowned experimental filmmaker Amit Dutta.

“Iconic experimental filmmaker Amit Dutta and I (Anurag) found ourselves on an unlikely topic during a phone call: chess. It’s not a game I know much about, so I asked him something almost too obvious and perhaps silly: Does chess really sharpen your mind, as they say at home?

His answer was straightforward: "I don’t know. It’s just a skill. But it’s addictive. Very addictive."

Dutta spoke of his near-obsessive relationship with the game, confessing that he fears for his eyesight from spending hours on screens. Yet, the game’s magnetic pull—the adrenaline rush, the challenge—keeps him hooked.

Then, he discussed how meticulously he researched chess, including collecting rare books to read its entire history. And yes, also the geopolitical history—from its influence during the Soviet era to its role in the modern day—all while reflecting on what the game has taught him about time itself.

Intrigued, I requested if he’d write about his connection to chess. He obliged. His memoir, written exclusively for Culture Cafe, marks his first-ever published article.

The result is personal and very interesting—a glimpse inside the mind of one of the best filmmakers of our times. Read the article below.“- Anurag Minus Verma

***

I grew up in a small village, about 30 kilometers from Jammu city—a border town. How I discovered chess there remains a mystery to me, but I vividly remember grappling with the game from a very young age. My closest friends were three Sikh brothers, two of whom were exceptional chess players. They introduced me to an older, Indian variation of chess rules, where pawns could move only one square at a time, and the King performed an intriguing and peculiar castling move by leaping like a knight before returning to its position. This unique twist fascinated me, and soon, the three of us became obsessed with the game, playing it whenever we could.

It was during this time that I first experienced the addictive quality of chess and its effect on those around us. Our parents, exasperated by our obsession, began throwing our only wooden chessboard around in frustration. Perhaps their disdain stemmed from the association of chess with gambling. Over time, the knight lost its neck, the King its crown, and some pawns disappeared altogether. These missing pieces were replaced by whatever we could find—rubber, coins, or even old, worn-out pencils.

Around the same period, one of my classmates' elder brothers, who was studying medicine in Tashkent, returned home for a visit. Fascinated by his tales of the mysterious land, we often sought him out. During one of his visits, he brought out a small chess book that introduced us to chess notations. Noticing my interest in the game, he shared a fascinating bit of history: Tashkent, he explained, had once been a vibrant hub on the ancient Silk Route. He claimed that chess had traveled along this very route, originating in Gandhara—the cradle of many ancient art forms—and spreading eastward to China. Being something of a history buff, he waxed lyrical about Gandhara’s contributions, confidently asserting that it was the birthplace of chess. He even claimed that our original homeland would have been ancient Gandhara. We listened wide-eyed, as though his tale had elevated our humble game into an epic saga of global conquest, with roots stretching back to a glorious, ancient past. For us—a group of refugees growing up in a colony after our village became part of Pakistan during the 1971 war—the idea carried a poignant and poetic irony.

Borrowing the book with great effort, I taught myself the international rules of chess. Later, I passed on these new rules to my Sikh friends, and we noticed that our games began to progress much faster. The book also introduced us to openings like the King’s Indian and Nimzo-Indian. My friend remarked that the word 'Indian' seemed to appear wherever pawn structures played a pivotal role in the opening patterns. These patterns often featured the slow, deliberate one-square movement of pawns, a characteristic that reminded us of the traditional version we had been playing earlier.

The Sikh brothers’ father was a truck driver who often transported goods from Kashmir. Whenever his truck returned, it brought fresh apples and other fruits. They also had two wonderful cows that produced the sweetest and most aromatic milk I have ever tasted. Their father, some sort of Ayurvedic expert, grew medicinal plants and concocted remedies, which he fed the cows through a bamboo pipe. Our hot summer afternoons were spent playing chess, drinking cold milk sometimes mixed with Rooh Afza, and enjoying Kashmiri apples.

During summer holidays, I often visited my bua in Jammu city. Her husband, my fufa, was the renowned Urdu poet Abid Manawari. One day, he gifted me a magnetic chessboard, an object I cherished deeply. (It was only later that I discovered my fufa was a disciple of another great Urdu poet, Josh Malsiyani, who himself was a student of Daagh Dehlvi. Daagh’s mother, Wajid Khanum, inspired the life of the protagonist in Shamsur Rahman Faruqi's celebrated novel Kai Chand The Sar-e-Asmaan. Remarkably, Josh Malsiyani was an avid chess player and had compiled a book of Urdu couplets dedicated to the game of chess. I am still searching for that book, as I hope to reprint it and bring it back into circulation. However, I was able to find one of his shers (couplets):

मुझसे जाँबाज़ को ग़ुरबत है, बिसाते-शतरंज।

जो न पल्टे कभी वापस, वह पियादा हूँ मैं।।

"Even the bravest falter when faced with me on the chessboard.

I am the pawn that never turns back." )

Later, I got admission to Jammu’s prominent GGM Science College, where I spent most of my time in the sports hall, playing chess instead of doing anything remotely academic. Chess fever ran high there, and the hall was always buzzing with players, each trying to outwit the other. Every day, I faced a classical dilemma the moment I entered the college gates. Two roads diverged: one leading to the lecture hall, the other to the chess hall. I would pause there for a few minutes, pretending to weigh my options. After all, I was traveling 60-65 kilometers every day for an education, but the moment I set foot on campus, all I wanted was to make a beeline for the chessboard.

Despite scolding myself, my feet always carried me toward the chess hall. There, no one cared much for opening theory or international rules; we mostly played the Indian version. The atmosphere was anything but calm and intellectual. The rule was simple: the winner stayed on while the loser gave way to the next challenger. It felt more like a cockfight than a chess game, with players and onlookers yelling and cheering as if someone had just checkmated a king with the furious peck of a fighting rooster.

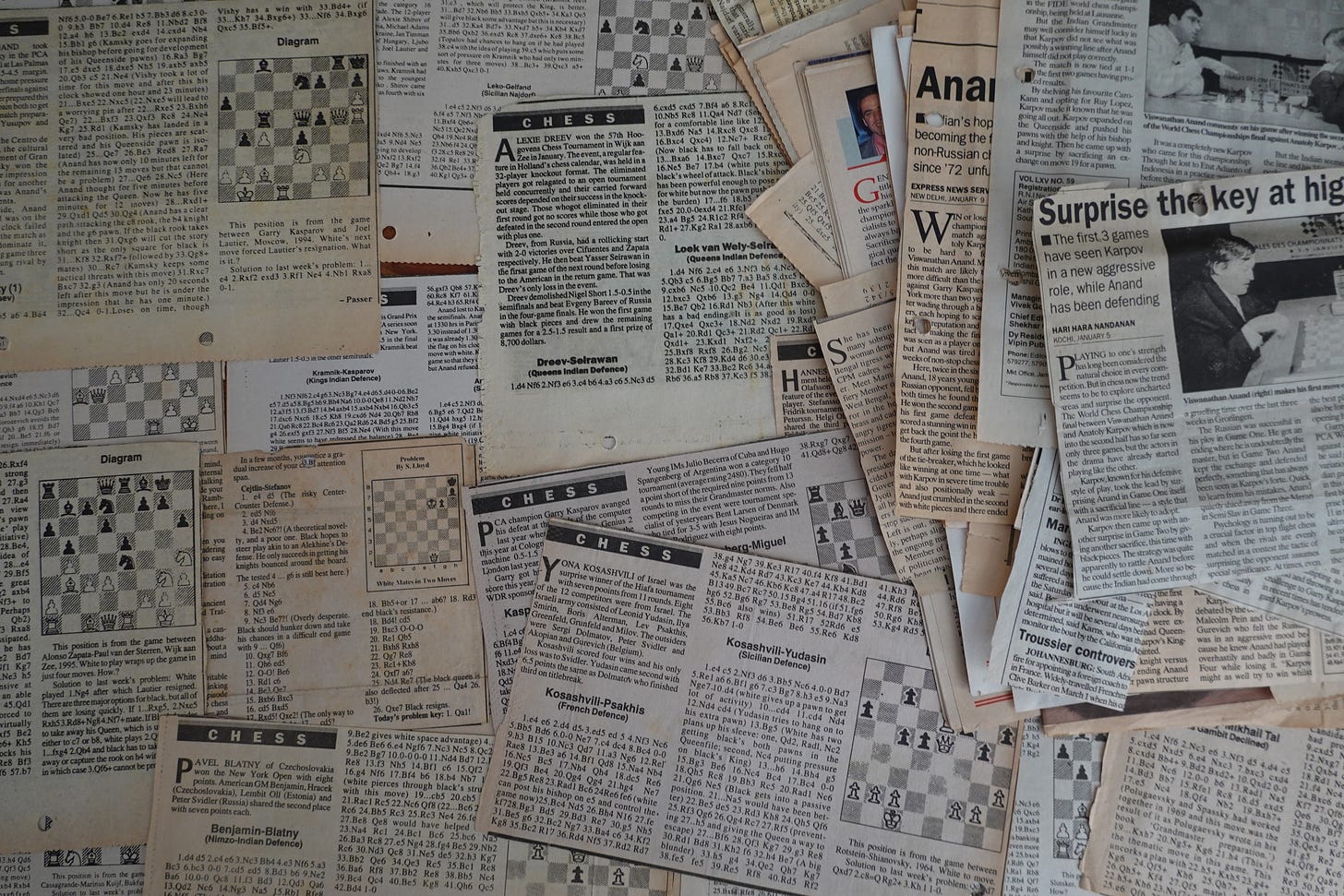

Chess books were very difficult to obtain in Jammu. There was only one person in a place called Panchtrithi who owned a book on Kasparov, and he refused to lend it to anyone. I remember traveling 40 kilometers just to get a photocopy of a chess magazine called Chess Mate, which was started by the legendary Manuel Aaron. Around that time, after much searching, I stumbled upon Howard Staunton’s 1847 magnum opus, The Chess-Player’s Handbook, in a dusty old bookshop. It felt like unearthing a treasure. Beside it lay another gem—a book on chess prodigy Nigel Short, written by his father. Armed with these books, I dived deeper into chess, even starting to buy newspapers that published weekly chess puzzles and annotated games. I filed them meticulously, treating them like sacred scrolls. That old file still sits on my bookshelf as a relic of my obsessive chess phase.

Back then, of course, there were no chess engines to explain the genius—or madness—of grandmasters’ moves. Playing through their games often left me scratching my head. Sometimes, their maneuvers seemed so baffling I wondered if they were playing chess or secretly mocking amateurs like me.

So, whatever little chess theory I learned came from Staunton’s book. I still remember the first time I came across the term "en passant" and how thrilled I was to learn this new rule. I eagerly introduced it to my playing partners, who looked as baffled as if I had just invented a new move on the spot.

One day, a commotion broke out in the chess hall. The college was organizing a chess tournament in the same hall, which would determine the top four players to represent the college in the state championship. There were so many participants that the professors decided to conduct interviews to shortlist players for the tournament. I still remember walking into that interview nervously, only to be greeted by a pipe-smoking professor who, without any preamble, asked, “What is en passant?”

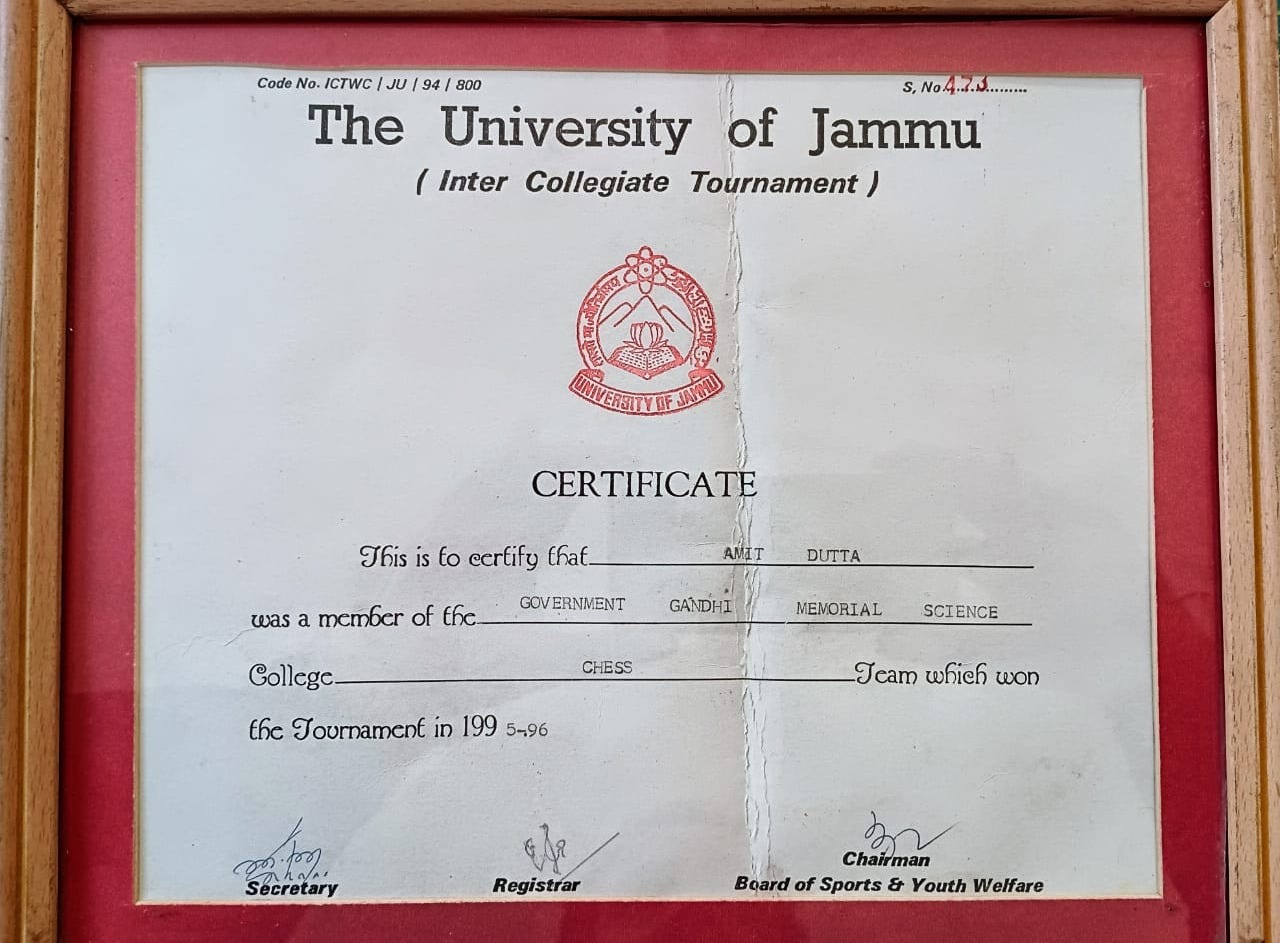

Having just read about it in the recently acquired chess books, I replied confidently, and he nodded approvingly. The tournament had nine rounds, and I managed to win all of them, securing my place on the college team. Our four-member team then traveled to the university to compete in the state championship, where we triumphed, even beating the senior university team.

One of the senior players, clearly upset by the defeat, challenged me to a blindfold match after the tournament. I politely declined, thinking it wiser not to antagonize someone nursing a bruised ego. Our victory earned us maroon-colored blazers, certificates, and even a photo in the local newspaper—my first taste of public recognition.

Following this, the top players from the state tournament were invited to a training camp, where the state team would be selected to compete in the national championship in Maharashtra. I was among those selected. The camp gave us a daily stipend of ₹35, and to this day, it remains one of the most cherished earnings of my life—money earned purely by playing chess.

But one bizarre incident from that camp left a strange aftertaste. During a practice game with a senior student, I took a short break and went to the washroom. The same student followed me there and, to my surprise, started pleading with me to forfeit the game. He explained that he came from a poor family and that being selected for the nationals would grant him a sports quota, possibly securing him a job to support his family. He added that I was still young and would have many more opportunities, but this was his final year and last chance. Moved by his plight, I agreed and forfeited my place. However, as fate would have it, he wasn’t selected for the state team either. A few weeks later, I bumped into him, and to my astonishment, he smirked and arrogantly remarked, “I would have beaten you anyway.” I was stunned. A friend standing beside me, after hearing the story, was furious and told me, “You were not just dishonest to yourself but also to the game.” Those words stung deeply. I never played competitive chess again after that.

Much later, I learned that such arrangements were not uncommon, even in professional chess. Bobby Fischer often complained about Soviet players pre-arranging draws to manipulate tournament outcomes. It was oddly comforting to know I wasn’t alone in encountering such behavior, but it did little to lessen the feeling that I had let the game down in that moment.

Around that time, my passion for chess began to fade, replaced by an all-consuming love for cinema. It wasn’t a sudden switch but more like a smooth transition. Coincidentally, this shift happened as I watched Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khiladi. The film had a memorable scene where Shabana Azmi’s character, fed up with her husband’s chess obsession, hides the pieces. Undeterred, the men improvise with supari, lemon, and mirchi—reminding me of childhood, when our parents tossed out the pieces, and we played with anything we could find.

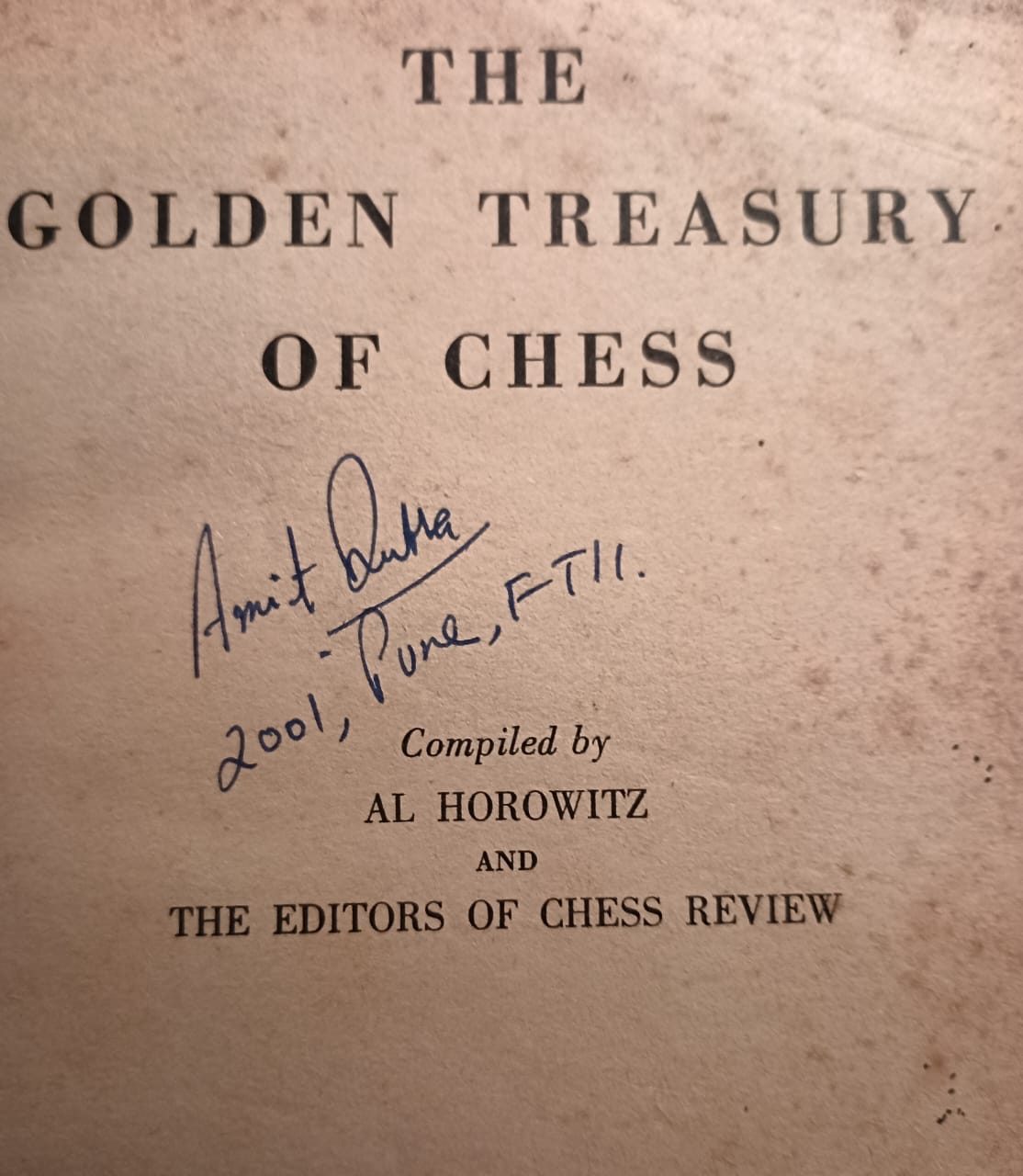

Eventually, I got selected for FTII in Pune to study cinema. Interestingly, though I never played chess there, my obsession with the game morphed into something else entirely. In Pune, I began collecting and reading rare chess books, diving deeper into the fascinating history of the game in India. That’s when I discovered Mir Sultan Khan, the Indian chess genius who won the British Chess Championship in the 1930s, and Fatima, the first Indian woman chess champion.

I still recall reading an analysis of a game between Sultan Khan and Capablanca. The commentator remarked on Sultan Khan’s delayed castling, which seemed unusual by European standards. The explanation? In Indian chess traditions, castling wasn’t a priority. That observation took me straight back to the chess hall in Jammu, where we too delayed castling—probably because moving the king like a knight felt unnecessarily cumbersome!

This interest pulled me into a labyrinth of ancient and medieval Indian chess lore, where I unearthed incredible characters like Gurbaksh Rai, a chess player in the court of the King of Jammu and Sultan Khan’s sparring partner. There was also Lala Raja Babu, who invented the first-ever mechanical chess recorder in the early 1900s and wrote Yaar-e-Shatranj. Then there was Kishan Lal Sarda, a halwai from Mathura who was one of the finest players of his time.

As my research deepened, I stumbled upon manuscripts like Chaturangadeepika, which described a version of chess where the rook was depicted as a boat. I found myself collecting so much information that a book seemed inevitable. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that this material deserved a story—a novel.

For the past seven years, I’ve been writing that novel, and it may take me a few more years to complete. The deeper I delve into chess history, the more it feels like piecing together an intricate endgame. In chess theory, if your strategy is sound and you position your pieces optimally, the final blow—a beautiful tactic—always lurks in the background. Similarly, understanding the intellectual environment of ancient India makes it less surprising that a game like chess could emerge.

Chess isn’t just a war game, as it’s often labeled. It’s far more profound. Harsa Carita by Bana (7th century) references the game, as does Firdausi’s Shahnameh, which credits India (specifically Kannauj) as its origin. The 12th-century text Manasollasa, attributed to Chalukya king Someshvara III, even describes a two-handed chess variant. H.J.R. Murray’s History of Chess (1913) discusses Mughal-era puzzles like the “Dilaram mate,” while Pune’s Vilasmanimanjari (1810) by Trivengadacharya Shastri and Sulapani’s Chaturangadeepika offer further fascinating insights.

My research extended to texts like Vakroktijivita and Dhvanyaloka, which explore advanced systems of thought. Concepts like guna, riti, and alankara from classical aesthetics seem to resonate with chess, albeit indirectly. A game like chess doesn’t emerge in a vacuum—it’s born from a highly evolved intellectual system. I even began pondering if the game played by Nala and Yudhishthira in the Mahabharata—often associated with dice—might have been an early form of chess, or chaturanga, with dice integrated into the gameplay. Indians have always loved blending chance and strategy, so this version isn’t far-fetched.

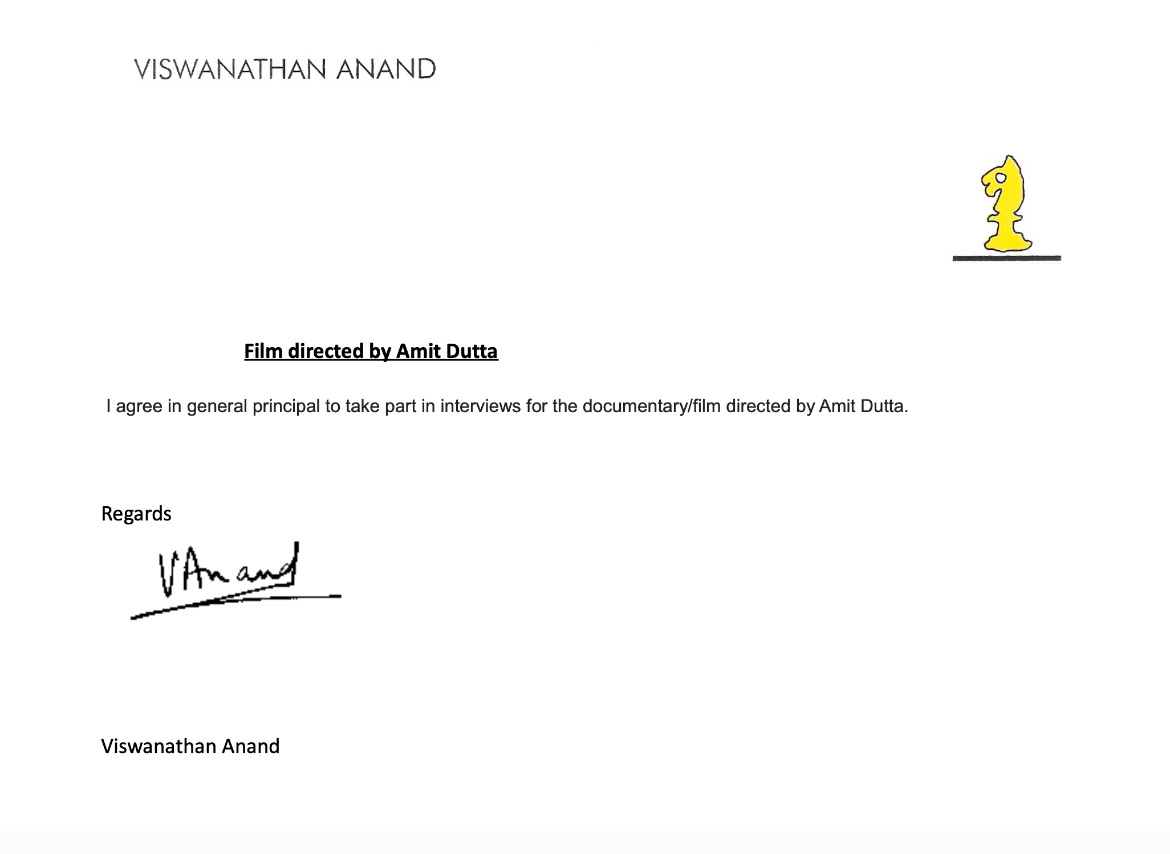

Around that time, I came across wonderful writing on chess and literature by Jaideep Unudurti. I proposed that we write a screenplay together, and during this time, we played numerous games and discussed chess and literature. It was a real pleasure knowing Jaideep. He was a master player, much stronger than me, who regularly beats IMs and Grandmasters online. He is an encyclopedia on obscure science fiction novels and books. We shared notes and essays, and one such conversation led me to make a film based on Steven Gerrard’s wonderful essay “Wittgenstein Plays Chess With Marcel Duchamp, Or How Not To Do Philosophy”. The film was released on Mubi, and I received a heartfelt letter from the legendary Bruce Pandolfini, whose books were cherished treasures of my youth. Jaideep also introduced me to IM Saravanan, and we had a conversation as a chess game, which was published in BOMB Magazine, New York. We also toyed with the idea of making a film on Viswanathan Anand, whom Jaideep knew and from whom he arranged a letter of consent. But, as often happens, many of our projects remain unrealized.

Jaideep and I have been interacting since, and a great joke connects us: if you play chess, it's a sign of a gentleman, and if you play chess well, it's a sign of a wasted life. We liked chess as an object of ideas, not a career—a pure non-utilitarian pleasure, as Nabokov said. I have been making films and writing, and my interests in these things have gone up and down, but one thing that has remained consistent since my childhood is my interest in chess. This surprises me because I am not a master by any stretch of the imagination but merely an amateur player. Nevertheless, you could say that I mainly play chess and steal time from it to make films and write books.

***

Amit Dutta is a filmmaker and writer with a keen interest in chess, particularly in the history of chess in India between 1800 and 1947. As an ardent chess player during his student days, he was part of the team that won the Inter-College State Chess Championship (1995-96). In 2017, he secured a silver medal in the All India Correspondence Chess Championship, and his chess biography was subsequently published in the AICCF Bulletin. His national peak Correspondence Chess rating is 2032, while his international rating, calculated using the new Glicko-2 rating system, is 2397. A collector of rare chess books, he is passionate about exploring the history, culture, and strategy of chess in medieval India, focusing on indigenous chess theory and forgotten chess knowledge preserved in vernacular languages.

Check out his work here: https://www.youtube.com/@matrapublications6330

-If you enjoyed this piece and then please consider supporting independent writing through Patreon or via UPI. Check links on sidebars.Your support keeps this work alive and encourage us to write more!

A great read. Thank you AMV bhai for asking Amit Dutta to write this wonderful piece. Was curious reading it.

Enjoyed reading this, it was lovely!