An Unexplored Side of Dr. Ambedkar: His Quiet Relationship with Cinema, Theatre, and Music

A Guest Post by Dr. Spva Sairam

Introduction by Anurag Minus Verma: When I was in New York, hanging out near Columbia University with some friends, someone suddenly asked—Where would Babasaheb have spent his leisure time here? Did he visit jazz clubs? What was his favourite place to eat? Did he also go to cinema theatres?

We know Babasaheb as the revolutionary thinker who altered the course of history. But very little is known about his connection to art, music, and film. I’ve always been drawn to the quieter details, the ordinary moments that make a person whole. In screenplay terms, it’s the part where character-building happens through small, specific details.

So when Dr. Spva Sairam sent me this piece, I was genuinely excited. It’s sharp, very deeply researched, and opens up a side of Babasaheb we rarely get to see.

Read it. Share it. And if it moved you even a little, support the writer. Every contribution—big or small—goes straight to the author. Here is UPI & PayPal and here’s BuyMeACoffee. Let’s make sure good research gets rewarded, not just scrolled past.

Now, over to Dr. Spva Sairam.

The Backdrop

What films did Dr. Ambedkar watch? And who were the artists from music and theatre he crossed paths with? The answers may never be fully known, but some traces remain. In this piece, I attempt to follow those traces—dividing his life into three phases: Phase I (1910–1930), Phase II (1931–1947), and Phase III (1948–1956)—to explore the films he saw and the cultural figures he engaged with along the way.

It begins in the early 20th century, with a young Ambedkar abroad. Just as cinema was learning to speak.

The Phase-I [1910-1930]

To begin with, it is believed that one of the earliest movies that Dr. Ambedkar watched was Uncle Tom’s Cabin [1927]. It is said that he went to this film along with his wife Ramai [1]. But this is not to suggest that he had not seen any movies before 1927. By the time he was in his twenties, Bombay’s theatre and film scene was already coming to life and it’s likely he was no stranger to it.

As historian Meera Kosambi noted:

"Maharashtra responded to international developments in film technology and Indianised this new medium of Western origin through style and content. The Lumiere brothers screened their first set of 12 short films at Mumbai’s Watson Hotel on 7 July 1896 for an audience of 200, at two-rupee tickets. A week later the films were screened twice a day at Novelty (later named Excelsior) Theatre with tickets ranging from two annas to two rupees...Other foreign films followed and an enterprising Parsi, M. Sethna, constructed Mumbai’s first theatre for films in 1904. Most popular among the foreign films was The Life of Christ in two parts …In 1913 came … path-breaking mythological Raja Harishchandra” [2]

Dadasaheb Phalke’s Raja Harishchandra which was considered as first full-length Indian feature film was released on May 3rd, 1913 and we know that Dr. Ambedkar embarked on his journey to Columbia University after June 1913. Is it possible to assume that in this gap of a month, he might have watched this movie that had been hyped a lot at that time? Unfortunately, we are left to make only a guess.

In the third week of July 1913, Dr. Ambedkar arrived in New York City. It is very interesting to understand the state of Theatre in the U.S.A. at that time. By the 1910s, feature-length films [films of four or more reels that usually ran for at least an hour] were extremely rare in the U.S.A., but everything began to change after 1910 – an era that is often referred to as the Classical Hollywood Cinema and New York City became a popular destination for most of the promising film studios.

In the words of Prof. Steve Neale: “…the corporate headquarters of the studios were not in Hollywood or Southern California, but in New York. It was here that finance was raised from banks and investors, that decisions about the cost, scale and nature of each season’s programme of films were taken, that publicity campaigns were mounted, that national and international distribution plans were made, and that the booking and circulation of film prints were organized…” [3]

The period 1913–1916, during which Babasaheb studied at Columbia University, saw the release of several notable films, including Traffic in Souls and While New York Sleeps (1913), Dough and Dynamite starring Charlie Chaplin (1914), The Call of the North (1914), and The Girl of the Golden West (1915). Among them was the controversial The Birth of a Nation (1915)—a film often praised for its technical innovation but widely condemned for its racist depictions of Black Americans and its glorification of the Ku Klux Klan. It triggered widespread protests, especially from civil rights groups like the NAACP, and remains a disturbing example of how cinema can serve both as art and propaganda

There’s no direct evidence to confirm whether he saw these films, but given the cinematic boom in New York during those years, it’s reasonable to assume that Ambedkar, a keen observer of society, would have been aware of the cultural shift underway as Hollywood began to define American modernity.

Phase-II [1931-1950]

The early 1930s marked the rise of remarkable filmmakers like V. Shantaram, who would go on to shape the language of Indian cinema. Known for blending social reform with visual innovation, Shantaram was one of the first directors to treat cinema as both art and activism.

Commenting on the social origins of Shantaram, Prof Meera Kosambi writes:

“Born to a Jain father and a Hindu Maratha mother in a small town near Kolhapur…Shantaram is ambiguous about his mother’s origins. Leela Chitnis mentions in passing that Shantaram’s maternal aunt, Mrs Pendharkar, was born into a Devdasi family” [4]

Shantaram’s first major role was in Savkari Pash (The Moneylender’s Shackles, 1925), a social drama directed by Baburao Painter and based on a story by N.H. Apte. But he didn’t stop at acting and soon turned director and went on to make a series of path-breaking films that cemented his place as a pioneer in Indian cinema.

It is noted that V. Shantaram shared a cordial relationship with Babasaheb. In the words of my friend Vinay: "V Shantaram was an avid supporter of Buddhist celebrations in Mumbai, including 6th December for Chaityabhumi. The Plaza cinema in Dadar built by him is modelled on Buddhism."

Interestingly, Shantaram’s daughter, Rajshree—known for her roles in films like Brahmachari (1968) and Around the World (1967)—was a student at Dr. Ambedkar’s Siddharth College in Bombay. Actor Jeetendra, too, studied at the same institution.

In one of our conversations, Sakya Nitin sir, whose father shared a good relationship with Shantaram told me:

“My father has good memories of V. Shantaram. My father and his friend would visit his studio and V. Shantaram would treat them very nicely. He used to donate money and give his film set material for Dr. Ambedkar Jayanti decoration. There was a very beautiful statue of Buddha inside his studio.”

I’m grateful to Sakya Nitin sir for sharing this valuable memory.

In this connection, it is interesting to note that Shantaram directed a movie called Amrit Manthan that deals with the conflict between Buddhism and Hinduism. Speaking about the same, Prof Meera Kosambi noted:

“Prabhat’s first film at Pune was Amrit Manthan (Marathi and Hindi, 1934) directed by V. Shantaram…supported by the singer Sureshbabu Mane and the female lead by the well-educated Nalini Tarkhad who made her debut, supported by the 16-year-old Shanta Apte. Set in the remote past, the imaginary, didactic and complicated storyline revolves around a pacifist, Buddhist king who is murdered by the orthodox Hindu royal priest who in turn faces a general public outcry and kills himself.” [5]

Amrit Manthan became the first Indian film to celebrate a Silver Jubilee—a term coined by Baburao Pai, distributor for Prabhat Film Company—after it ran in Bombay for over 25 weeks.

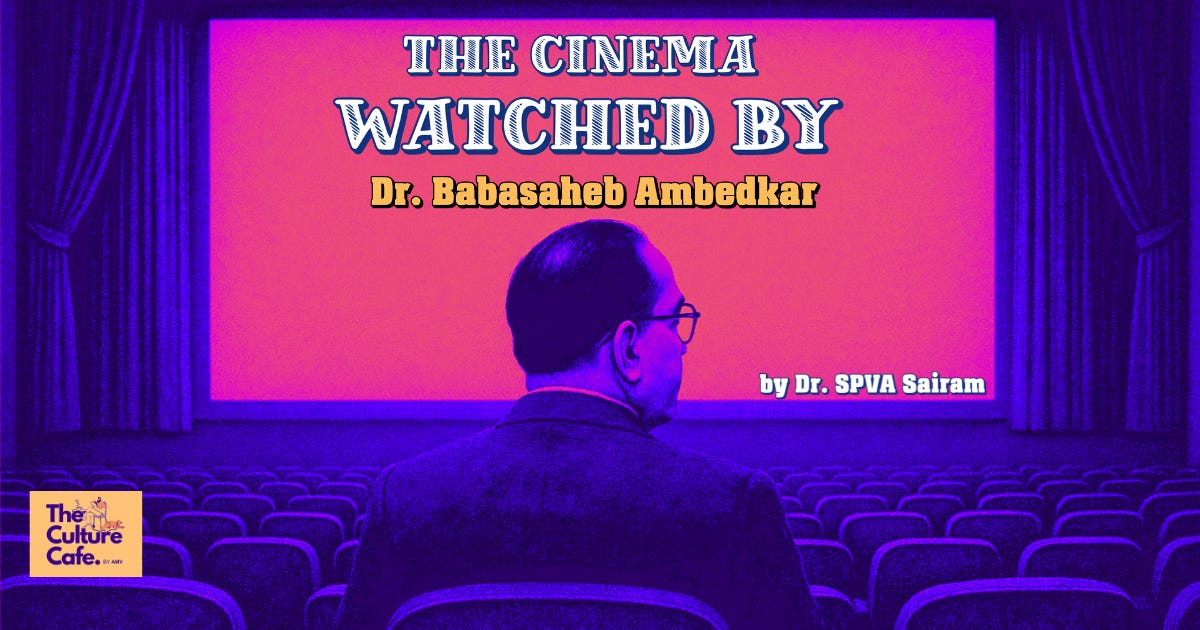

We do not know if Dr. Ambedkar had watched Amrit Manthan, but a careful examination of his writings and letters shows us that he watched at least two films of V. Shantaram namely Dharmatma (1935) and Kunku (1937).

Speaking about the film Dharmatma, Babasaheb noted:

“Even the saint Eknath who now figures in the film “Dharmatma” as a hero for having shown courage to touch the untouchables and dine with them, did so not because he was opposed to Caste and Untouchability but because he felt that the pollution caused thereby could be washed away by a bath in the sacred waters of the river Ganges”. [6]

Shockingly, some of the members of the censor board forced the director to cut a scene from the film which depicts an Untouchable girl entering a Brahmin’s house. [7]

The resistance to showing caste realities in Indian cinema continues—as seen in 2025, when the CBFC asked for changes in Phule, a biopic on Jyotirao and Savitribai, including edits to caste terms and scenes of historical discrimination.

The information regarding Kunku [released in Hindi as Duniya Na Maane] is available from the letter that Dr. Ambedkar had written to Dr. Savita Ambedkar, Babasaheb wrote:

“If words have any meaning and marriage has any foundation, what am I to understand when you said in your letter in which you said, "I accept you". You accept me as what? As a Great man, as a learned man, or as a Good looking man? What is your spring of action? As a poet has said. "Love built on beauty dies as soon as Beauty dies". The same is true of love built on Greatness or Learning. These things after some time begin to fail. They cannot be the foundation of marriage. Marriage can be founded only on love which can be described in no other terms except the longing to belong. Are you actuated by this feeling? Nothing else will either do or suffice. I do not know if you have seen the film KUNKU or read the novel called "WOMAN THOU GAVEST ME" by Hall Caine. The marriage in both cases was a matter of form. How very unhappy and tragic they were. The reason why they were so tragic was because there was no longing to belong". [8]

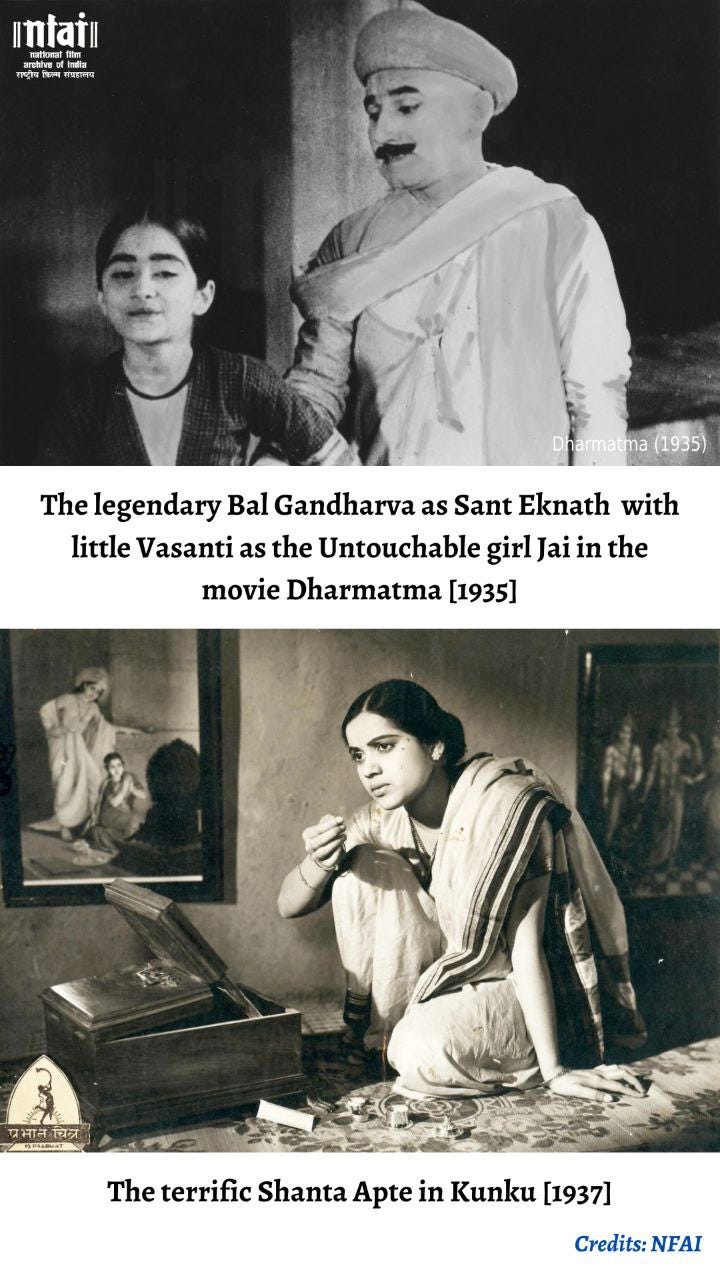

Another interesting link between Babasaheb and Shantaram was the great Sangeet Kalanidhi Master Krishnarao Phulambrikar. Master Krishna was a very popular classical singer who is credited with having created numerous complex (aprachalit or anwat raags), composite raags (jod raags), and many bandishes [fixed, melodic compositions in Hindustani vocal music]. Master Krishna has made a debut in the film industry with Shantaram's Dharmatma [popular Marathi stage performer Bal Gandharva had also made his debut with this movie. Interestingly, it was Shahu Maharaj who encouraged the talent of young Bal Gandharva and helped with the treatment of his ear infection under the renowned physician Dr. Charles Edward Vail of Wanless Mission Hospital [9]]

Master Krishna was deeply influenced by the movement of Babasaheb and performed opening songs for him on many occasions [10]. Impressed by his amazing voice, Babasaheb had requested Master Krishna to compose music for Buddha Vandana. In this process, he learned Pali at Dr. Ambedkar’s Siddhartha College. The story goes like this:

“Influenced by the endless efforts by the Master to make 'Vande Mataram' the national anthem of the country, in front of the members of the Constituent Assembly, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar requested him to set Buddha Vandana to music. The master accepted the request and composed the Buddha Vandana without taking any remuneration, in the spirit of serving the Lord Buddha…As the lead singer, he sang the entire Buddha Vandana and effectively used the chorus wherever required. For this, he had also taken the efforts to learn the Pali language to understand the meaning of these sacred chants. For this work, he went to Siddhartha College in Mumbai… Dr. Babasaheb hailed this work, felicitated Master Krishnarao, and brought out a 78rpm record of Buddha Vandana in 1956. This record was played during the mass conversion ceremony held at Nagpur on the 14th of October 1956” [11]

Besides watching Uncle Tom’s Cabin [1927], Dharmatma [1935] and Kunku [1937], Dr. Ambedkar might have watched Bombay Talkies’ Achhut Kanya [1936] starring Devika Rani and Ashok Kumar. [12]

Achhut Kanya (1936) tells the story of a romantic relationship between an upper-caste Brahmin boy and a Dalit girl, set against the backdrop of rigid caste hierarchies. The film challenged social norms by portraying the emotional cost of untouchability and forbidden love.

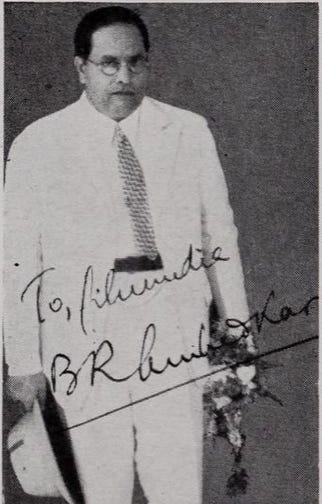

Dr. Ambedkar’s interview with Filmindia [1942]

Around 1938, we find that Dr. Ambedkar had seen an American film called “The Birth of a Baby”. Speaking about the same in an interview given to a film magazine called Film india, Dr. Ambedkar remarked:

“Our people, the adults, and the grown-ups and not merely children, need to be taught for instance, in our urban as well as rural areas, how to live, take care of the body, keep away from disease. Producers of pictures in this country would be doing a great patriotic service if they made such pictures and showed them to our masses…

… I saw a little while back a picture called "The Birth of a Baby." That is my idea of an educational and a propaganda picture. There was not a single celebrated star in that picture. All the people who were doctors, nurses, patients, husbands, and wives in that picture were quite ordinary folk. With what wonderful effect, the picture teaches how girls and boys in their teens, in marital, prenuptial, and post-nuptial stages should behave and take care of the new born. What effective propaganda against abortions of the undesirable sort and in favour of birth control of the right kind did the picture contain! I wish some producing company here got permission to copy that picture, with slight alterations to suit the Indian scene. It would be a very necessary social service."

Commenting on the important role played by films in our lives, Babasaheb noted:

“To my mind, films have a particularly important function to perform in India. Our people are too serious. They do not know how to laugh at things and themselves and enjoy life. This seriousness means concentration of nerves and therefore exhaustion of energy for no useful purpose whatsoever.

…Theirs is a drab, dreary existence— an imposition as it were. I have a feeling that we regard coming to life here as a punishment by God. Films are the best medium of teaching our people to see life, to laugh at it, to laugh at themselves, to indulge in self-inquiry and self-criticism.

…Films are within the reach of all and I wish they spread about in every nook and corner of the country, because they perform his much-needed task of providing relaxation to our highly-strung people.”

Speaking about the effectiveness of film as a medium to promote social good, Babasaheb noted:

“I am, in no sense, a film man, not even a fan. I reckon it as a misfortune. But when sufficiently advanced in life, you cannot change your habits and tastes. My only passion is books. I am a voracious reader of them. I write a book, now and then, when there is an irrepressible prompting. But I do wish films were my passion. They are undoubtedly a far more effective and potential means of education than books. Most men have to learn by visual images, pictures of things. You make full use of all your senses, when you see a film and that makes education easier and more effective. If my message has any value to readers of "FilmIndia" I shall ask them to take as varied and as absorbing as possible an interest in films and their manifold uses for social well-being and social service."

Dr. Ambedkar rightly believed that films should educate and enlighten people rather than drenching them further in the ocean of superstitions and irrationality. He says:

“…Our producers have yet to get out of the mythological stupidities, oddities and deification of mere men...Instead of having the stories of Ekanath and Chokha Mela with all their eccentricities and miracles as superstitiously transferred to the screen as they are chewed with delicious devotion by our Kirtankars and Puraniks, which promote superstitions on a vast scale with 20th century apparatus, our producers will do well to depict how the depressed class movement has outgrown its humanitarian and religious shell and broken into a self-reliant movement, demanding the Rights of Men.” [13]

The 1940s also marked the period when the legendary C.N. Annadurai crossed paths with Dr. Ambedkar. C.N. Annadurai was a writer, orator, and founder of the DMK, who later became the first Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu. Before politics, he shaped Tamil cinema with screenplays that challenged caste hierarchies and carried the pulse of the Dravidian movement.

One of the first recorded events of the meeting between Annadurai and Dr. Ambedkar occurred on 06-01-1940 when the latter hosted a tea party for Periyar and his associates. The next day, Dr. Ambedkar and Periyar were taken into the procession and addressed a public meeting at Dharavi. The extraordinary highlight of the meeting was the fact that Annadurai translated Dr. Ambedkar’s English speech into Tamil and Periyar’s Tamil speech into English for the understanding of both leaders [15].

Sixteen years later when Dr. Ambedkar embraced Buddhism in Nagpur along with more than 7 lakh followers, Anna was one of the few giants in India who welcomed this historic event. Writing in Dravida Nadu on 21-10-1956, Anna eloquently said:

“Today Buddhism has taken on the compassionate task of drawing into its fold those who have tired of the Hindu religion, and seek to exit it. Never before in history has such an event taken place: on a single day and gathered in one place, over three hundred thousand men, women, and children abandoned one religion for another, left Hinduism, and embraced Buddhism. A reporter writing about it remarks that nowhere in the world has such a thing happened, and marvels at this sea of people, gathered in a large ground outside the city, a site that extends ten lakh square feet….

Dr Ambedkar is learned in the Hindu religion and has studied it deeply. One can safely say that there is not a Hindu text, whether Vedic or Agamic, that he has not mastered. His knowledge of law is extensive and his legal acumen and training fitted him to the task of drawing up the Indian constitution. That such a learned man decided to lay by his Hindu faith and convert to Buddhism with three hundred thousand people makes for a unique choice and one that is quite different from that exercised by others who convert, only because of their dislike of their religion…

Untouchability, unseeability, not letting people come close to you, insisting on birth-based notions of high and low… even if it were a palace wrought in gold, it is a building infested with the vilest of viruses and men like Dr Ambedkar cannot be expected to live in such a space. They will leave it one day or another. Dr Ambedkar’s conversion deserves praise from all those who are possessed of good sense and intelligence.” [16]

The Phase-III [1948-1956]

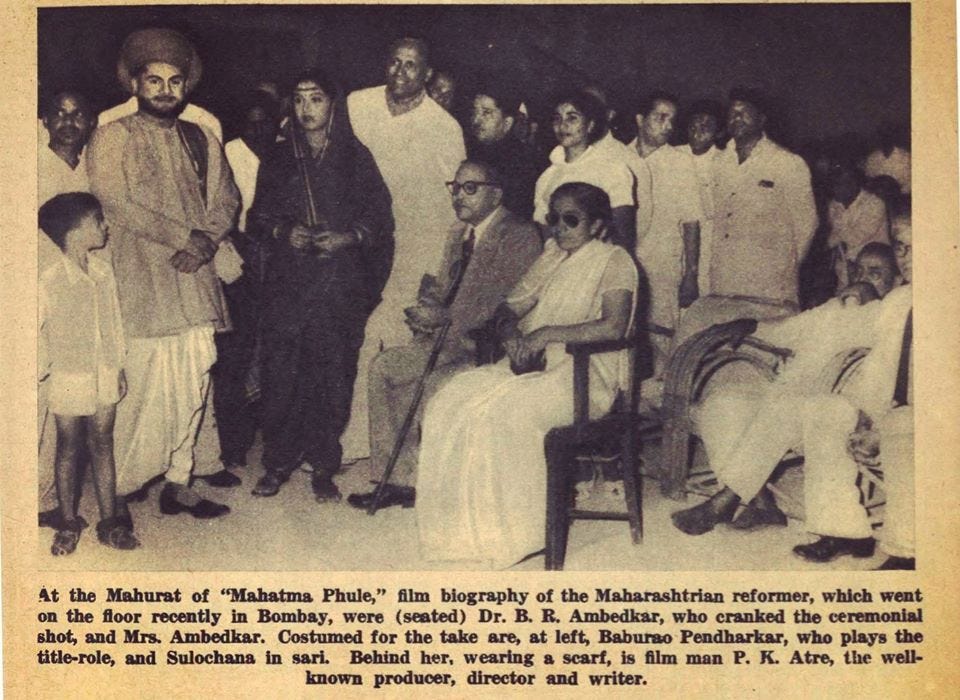

In 1948, Dr. Ambedkar married Dr. Savita Ambedkar and evidence points that they watched at least two movies together, Oliver Twist (1948) and Mahatma Phule (1954). Unlike Oliver Twist, we have some interesting information to understand Dr. Ambedkar’s reaction to the movie on his guru Mahatma Phule. Narrating the same, Dr. Savita Ambedkar writes:

“The great doyen of literature Acharya Atre had decided to make a film on Mahatma Jyotiba Phule and had invited Saheb for the launch of the shooting. Saheb was not keeping very well, but since it was a movie on Mahatma Phule and because he enjoyed a very close relationship with Atre, he could not turn the invitation down. The launching of the shooting was done at the hands of Saheb at Famous Studios, Mumbai, on 31 January 1954"

After the film was ready, Dr. Ambedkar and Dr. Savita Ambedkar were invited for the premiere. Recollecting about that event, Dr. Savita Ambedkar noted:

"Once the film was ready, Atre also invited us for its premiere. Saheb was completely overwhelmed when he saw the movie. As he saw it, he remembered Mahatma Phule’s work and sacrifice and wept. After the movie was over, he patted Pendharkar on the back for his excellent performance and congratulated Atre too. Not satisfied with this, he wrote a letter to Atre on 20 November 1955, lavishing praise on him and wishing the movie success.” [17]

Dr. Savita Ambedkar also shares an interesting interaction between Patthe Bapurao and Babasaheb, she wrote:

“There is another example of Saheb literally driving away the famous theatre man Patthe Bapurao by telling him, ‘I don’t want so much as a shell from a person who makes his money by getting untouchable women to dance on the stage.’ A number of capitalists had expressed their readiness to help on condition that the institutions be named after them, but Saheb never accepted money that was earned by illegal means” [18]

The late 1940s saw the rise of many fresh talents in the film industry, the most spectacular among them was Mohammed Yusuf Khan, popularly known as Dilip Kumar and Lata Mangeshkar. Noting the fact that she met Babasaheb, Lata Mangeshkar tweeted:

“On the anniversary of Bharat Ratna Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar ji, father of the Indian Constitution, I offer him a million prayers. I met him in person and that is my good fortune” [19]

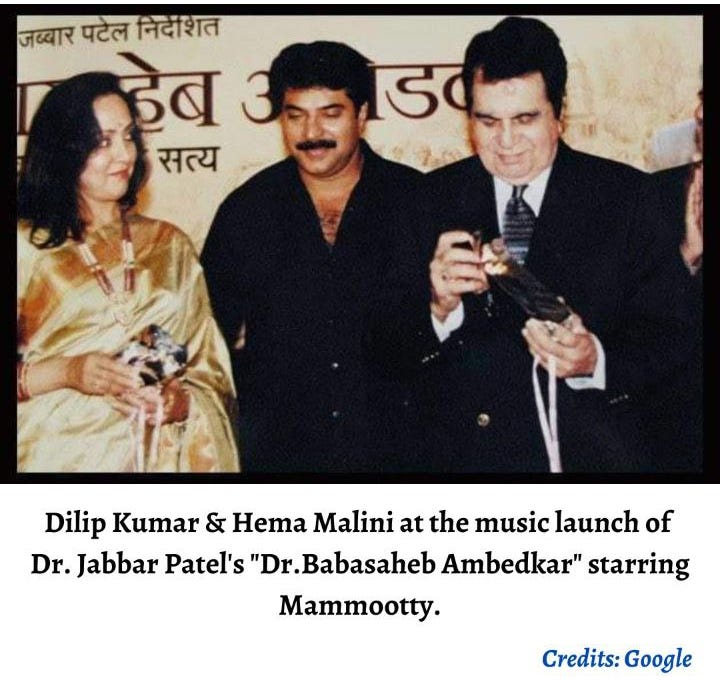

It is also recorded that Dilip Kumar met Babasaheb Ambedkar on a few occasions. There are two accounts that offer some information regarding their meetings, while the former account informs that both had heated arguments over the morality of film stars [20], the latter account narrates how Dilip Kumar got inspired from the words of Dr. Ambedkar [21].

After a serious examination of both accounts and the events that followed later, one can assert positively that despite the difference of opinion on a few issues, Dilip Kumar had a huge reverence for Dr. Ambedkar, which becomes clear after reading the speech that Dilip Kumar gave at the music launch of the movie “Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar” directed by Jabbar Patel.

Speaking about the greatness of Babasaheb, Dilip Sahab said:

“The completion of the film on Dr.Ambedkar or I should rather say, to have the courage to venture and try and make a film on a man who has given this country its constitution, which defines the rights of every given individual on this land, rights in equity and thereby rights in decency and made this country as one of the fraternity of the civilized people on this earth...It's strange how historians, even the media, the people, and politicians have bypassed this great man who through his sacrifice and scholarship, who with his will and great determination went on...I had the unique experience and pleasure to have met Dr.Ambedkar during his closing years in life. I don't think I need to dilate upon my own experience with him but definitely his life is a shining example for all those people who are civilized....we were the first country to have a constitution that defined the rights of every single individual, not a sect of people or not a community but every given individual ...We were all young when the country was free, we had a great deal of reverence for Dr.Ambedkar.” [22]

It is generally regarded that Dilip Kumar along with Raj Kapoor and Devanand formed a powerful trio who excelled well at the Box office. We have already seen the connection between Dilip Kumar and Dr. Ambedkar, and it is fascinating to find if Raj Kapoor or Devanand interacted with Dr. Ambedkar. I could not find any such reference with respect to Devanand but I found something fascinating regarding Raj Kapoor. To quote the words of Rahul Rawail:

“In Bombay, he [Raj Kapoor] loved to go to town to this place called Wayside Inn. He'd always sit at the centre table there and the cooks would all come out to greet him. They would all slap his back and say, 'Raj, kaisa hai? Bahut time ke baad aaya.' Seeing his chemistry with them, we learnt that he had been coming there since he was a child and the cooks were the same old guys from his childhood. The restaurant had a typical British menu. When I asked him why that place was dear to him, he told me, 'You know, there is a reason why I come here often and why I sit at this particular table and chair. This is the place where Dr Ambedkar sat and wrote the Constitution of India. I sit here so that it can inspire me to do constructive work.’” [23]

It is worth noting that Raj Kapoor acted in a movie under the direction of Khwaja Ahmad Abbas called “Char Dil Char Raahein” [1959] that deals with the question of Untouchability. The extraordinarily gifted Meena Kumari [24] played the role of an Untouchable woman and interestingly the movie speaks about the idea of a new religion of equality that transcends the barriers of caste – the idea that resonates powerfully with the firm resolve of Dr. Ambedkar to embrace Buddhism.

Another less-known connection that Babasaheb had with the film industry is with Kumarsen Samarth. Kumarsen’s brother M.B. Samarth was a close friend to Dr. Ambedkar. Kumarsen married the then-famous Marathi actress Shobana Samarth [who was the daughter of actress Rattan Bai]. Popular actresses Nutan [25] and Tanuja were their daughters [Kajol is the daughter of Tanuja]. Shobana is also related to another top-notch performer called Nalini Jayawant who acted in classics like Shikasth [1953], Nastik [1954], Kaala Paani [1958].

In fact, when Babasaheb Ambedkar planned a major conversion ceremony to Buddhism in Bombay on 16 December 1956, he intended to stay at the home of Kumarsen and Shobana Samarth. But he passed away ten days earlier, on 6 December 1956.[26]

Dr. Ambedkar’s legacy is often framed in terms of law, revolution, and resistance—and rightly so. But scattered across his life are quieter moments: a film he may have watched, a melody he might have enjoyed, a tune he may hummed when alone, a conversation with an artist that left an imprint. These fragments remind us that even the fiercest minds need pause, art, and company. And that sometimes, the story of a nation is also hidden in the stories its leaders didn’t have time to tell.

(A shorter version of this article was first published on Round Table India on 28 November 2023.)

About the author: Dr. Spva Sairam is a Dentist and an Independent Researcher who writes articles exploring the lives of Dr. Ambedkar and the Phule couple. Recently, he delivered a YouTube talk where he gave a brief introduction to almost all the books written by Dr. Ambedkar. He can be contacted at drspva97@gmail.com

If you liked this article and if it moved you even a little, support the writer. Every contribution—big or small—goes straight to the author. Here is UPI & PayPal and here’s BuyMeACoffee. Let’s ensure thoughtful research gets the attention it deserves

All the references for this article can be found here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1dqPoUGP4VpRZikQ5S40IrDwNoSc6O78IeX3OAeAO9M4/edit?tab=t.0

Thank you doctor for this wonderful read! I was simultaneously adding these films to my watchlist haha! looking forward to more from you ❤️

Thank you for such a well researched article. I have a question, from a research perspective, any thoughts on how accurate Jabbar Patel’s movie is considered as a chronicle of Babasaheb’s life?