A Short Portrait of My Lonely Hostel Warden

Boredom of pre social media days

Instagram is both a nuisance and an addiction. A slot machine of validation, designed to keep you in an endless loop of scrolling, judging, and wondering if your breakfast is photogenic enough.

Then there’s nostalgia—sneaky, uninvited like a FEDX scam call. A random photo, message, and suddenly you remember a childhood lane you had completely forgotten. The brain, it turns out, hoards the most trivial details for a day when an algorithm decides to make you sentimental about nothing in particular.

On insta, few months back, I got a message from someone who, I suspect, was seized by a nostalgia so intense it could only be chemically induced or perhaps by dipping a Parle-G biscuit into Wagh Bakri tea, which can be Indian equivalent of a Proustian madeleine.

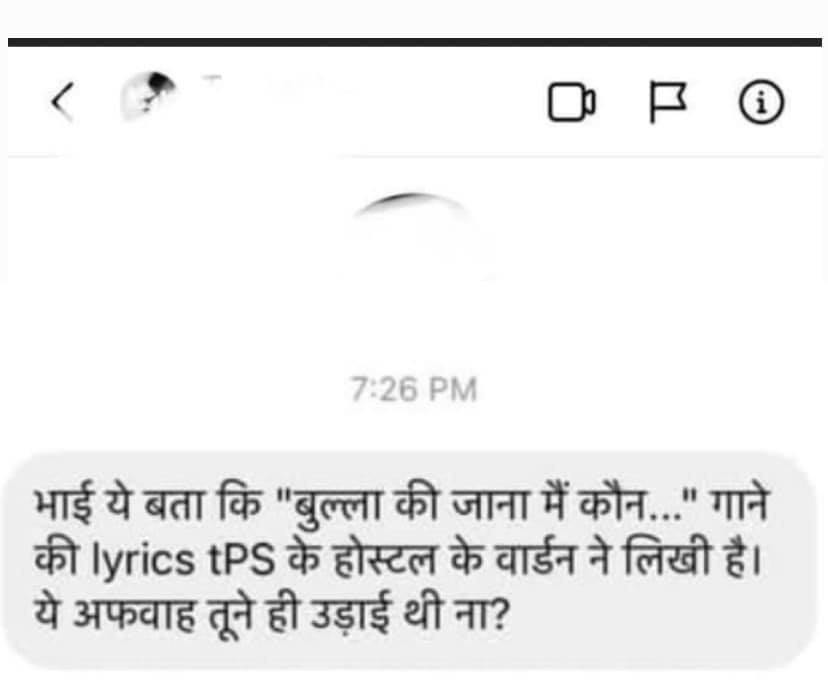

The message itself was cryptic which doesn’t make much sense. It doesn’t even make sense for me then how can it will be for you, my readers.

It reads: Bhai, yeh bata, hostel mein yeh afwah tune failayi ki ‘Bulla Ki Jaana’ gaana warden ne likha.

This came from a schoolmate I had no memory of, which was not surprising, because I didn’t really have friends in school. My only ambition there was to escape, and nostalgia, if it existed at all, was just the absence of school itself. But I did have some memories of my hostel warden. One of his eyes was filled with a grey stone, as if time had gathered and hardened inside him. Some students claimed he lost it while serving in the army. Others claimed he lost it when a former student, frustrated after being denied permission to go out on Valentine’s Day—an act that, he believed, directly led to his premature breakup—returned to the hostel and punched him in the face during his morning walk. The punch, a student claimed, was so punchy that even in the middle of the park, where everyone was doing laughing yoga, it was still heard.

We found the second story more believable, mostly because we wanted it to be true.

The warden was a creature of discipline, which in India is simply another form of sorrow. And like all men who have suffered for too long, he wanted to pass it down. He wanted to be superspreader of melancholy. That too to us. The, young, newly inducted members of the world, still high on the raw chemicals of youth. We were breaking into adulthood with a passionate desperation—to fall in love, to jump, to see what world has to offer us, to run aimlessly like Jean-Pierre Léaud in the film The 400 Blows movie. And here was this old man, who in screenplay terms was in 3rd act of his life, clinging to his last bit of power, insisting that our days be as banal as his.

He must have been seventy, or at least that’s how he looked. A broad, towering man with the aura of someone who could beat you senseless if he chose to. But what truly made him terrifying was his silence. He spoke in brief, functional sentences. And, as is always the case, the less a person speaks, the more mysterious they appear. Less information is a power move!

But now, looking back, I think it wasn't a case of mystery, he was just a loner who had already spoken too much in life and now bored with the very futility of words. Words, blabbering, yapping doesn’t have much in it after a point. I remember a saying: Once a wise man said nothing!

Why else would he wander the hostel corridors at night, very late in night, like ghost. His bunch of keys clinking, making sounds, like an out of tune percussion instrument? Some said he did it to maintain discipline, the way police vans drive around at night with their sirens blaring, simply to remind everyone that power still exists. But he was too old to make statements. Perhaps he simply liked to walk around in the night in empty corridor because he was an insomniac like Travis Bickle.

He was fiercely opposed to entertainment. The TV room was opened once a week, and even then, it played the kind of films that made you believe why Ravish Kumar said, "Aap TV dekhna band kariye" (You should stop watching TV). Manoj Kumar was his favorite actor, which tells you everything you need to know about his persona.

To leave the hostel on Sundays, we needed his permission. And even then, it depended on his mood. Sometimes he allowed it. Sometimes he didn’t. I had no idea why, but he allowed me more often than not. Trivia is that he once even allowed me to go out and watch Taarzan: The Wonder Car movie.

Maybe he saw in me the quiet loneliness that mirrored his own. Or maybe he thought I was a good boy. He would often tell me that I was an ideal student—silent, obedient, the kind that didn’t do activities, which in his Gita Press dictionary, was considered as: wrong activities.

One day, during the routine room inspection that came like clockwork every month, he stepped in with the weary declaration, "Idhar kuch milna toh hai nahi, lekin phir bhi karte hain" (There’s nothing to be found here, but let’s go through the motions anyway).

His assistant began the ritual, pulling out my belongings from the almirah with mechanical indifference—slambooks, clothes, scattered papers. And then, from a forgotten corner, a miniature bottle of vodka surfaced.

He paused. Looked at me. Not with anger, not even with disappointment, but with a kind of quiet disbelief. As if, for a fleeting moment, he thought everything in this world hurts. Or maybe he had already seen too much to be truly surprised—this was just another addition to the long list of letdowns.

Without drama, without expression, he picked up the phone, dialed my father, and in the same dry tone he used for hostel notices, informed him, "Aapke bete ka favourite drink Magic Moments Apple Vodka hai."

(Fav brand of your son is Magic Moments Apple Vodka)

We were entertainment-deprived. Some kind of stimulation was necessary. This was not the phone era. No Instagram, no Snapchat. Just life, staring back at us like an empty abyss, and we had to fill it with something.

And as Nietzsche said, "If you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss will finally get bored and ask, "Abey aur kitna dekhega?" (How much longer are you going to stare?)

So we made things up. I created comic strips, mimicked laughter challenge comedians, and movie characters, sometimes even tried rap songs. We spread rumours just for the thrill of it.

Our hostel window overlooked a cremation ground, and we spent long nights convincing ourselves that we had seen ghosts. It was a world starved of dopamine, and we were desperate to steal some form of pleasure in this.

It was around this time that Rabbi Shergill’s Bulla Ki Jaana came out. And for reasons I no longer remember, I started a rumor that the song was written by my warden.

One night, in an act of pure boredom, I mimicked his voice and recorded myself singing Bulla Ki Jaana Main Kaun. The rumor spread. People began to believe that the warden, this joyless fossil, secretly had a poetic side. That he understood contemporary culture. That he was growing, changing, and perhaps—just perhaps—one day, he would even allow us to watch new films. A desperate transition we required from Manoj Kumar to Akshay Kumar.

For the first time, there was hope. Hope that he was human, all too human.

And so we waited. And we waited. And we waited.

The brain really does sometimes stores mundane memories from the past which had no serious impact on you as a person.

While reading this, I remembered the time when I stayed with my maternal grandma’s sister’s home one summer. I must be 11-12 at that time and she had 5 children. The youngest was a boy and he was a year younger than me. My young uncle and other older aunts ranging from 13 to 20; we hung out solid for a month. I am reminded of many instances happened at that time. Such raw memories, untouched by your “post that life” experiences are rare and are so refreshing that you don’t want to share it with the world.

Thank you for writing this!

Anurag, you bring back so many memories and after a long long time, your writing is nudging me to start writing again. Love it as always -- can see everything including the man and the telephone he must have used to call your father.

Keep writing.